A Clash of Kingdoms

By Joshua Ake

“In those days Caesar Augustus issued a decree that a census should be taken of the entire Roman world” (Luke 2:1). When Luke writes this passage, he does more than simply introduce the narrative scenario of a census, which will serve to drive the events of the forthcoming story. He also sets the entirety of his gospel against the backdrop of a significant flash point in history, against the political, cultural, and world-changing realities of the Roman Empire in the 1st Century world. By simply mentioning the name Caesar Augustus, his audience would have been able to import that context instantly into the story with little need for further background information, because it was a context in which his audience was still living.

When a young Roman named Octavian rose to become the first emperor of Rome—known as aesar Augustus—it changed the course of history in profound ways. Another highly significant event which took place in the 1st Century is, of course, the rise of Christianity only a few short decades later. Since these two events occur almost in tandem, the significance and impact of each can often be seen in relation to each other. Much of the language with which Jesus is described throughout the New Testament is similar to language that is also applied to Caesar, and significant debate has often arisen regarding what the New Testament authors intended by making use of such parallels. Are they making intentional challenges and critiques of Caesar—and Rome more broadly—or are they simply using relevant connections from their surrounding world to better illustrate their depictions of Jesus?

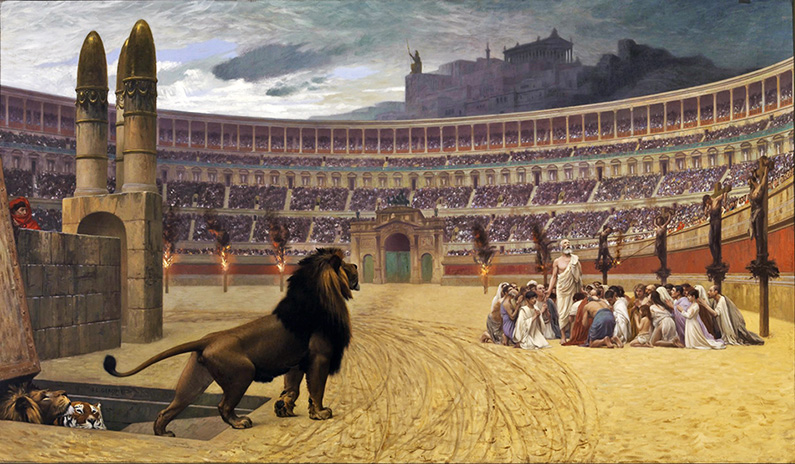

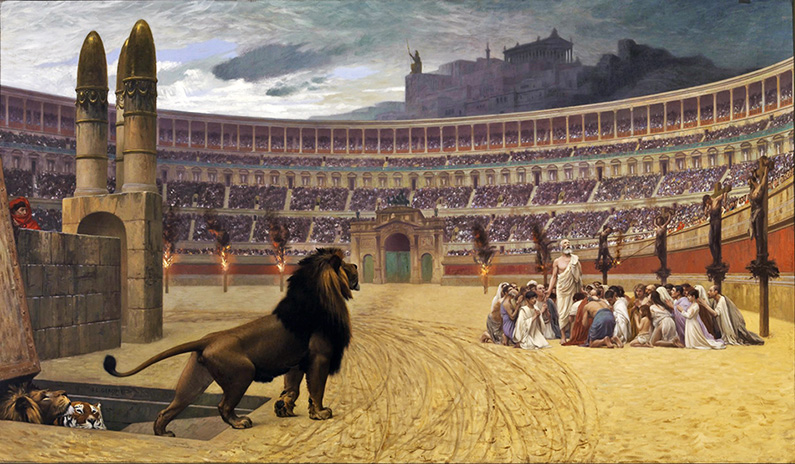

Christian martyrs in Roman Coliseum

Undoubtedly, Caesar Augustus embodied far more than a simple political leader in the minds of the people living throughout the Roman Empire. Following the assassination of Julius Caesar, when Octavian is named his heir, he swiftly and subtly utilized the wealth and influence which he inherited, as well as the name. And after Julius Caesar was also posthumously deified by the Roman Senate, Octavian had the unique privilege of being able to call himself a “son of god.” Although the Senate would only officially deify worthy emperors after their deaths, people throughout the empire quickly began worshiping Augustus, as well as later emperors, even while they were still living.

The imperial cult became especially prominent in the eastern regions of the empire. It was not long before numerous cities were leaping at the chance to impress and honor Caesar by building temples to him, in Asia Minor, in Greece, and even in the land of Israel at Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea Philippi, and Sebaste, all three named after Caesar. These places throughout the empire seem to have done this independently, with no coercion or force on the part of Caesar himself. Perhaps they hoped to gain Caesar’s favor, or perhaps they were grateful for the stability and the peace that they experienced under the Pax Romana, or maybe it simply became a matter of competition between other cities. S.R.F. Price suggests that some people may have preferred to view the emperor in a religious context to better comprehend and rationalize the reality of foreign dominance, which would otherwise be distasteful in formerly self-governing cities. He said:

They attempted to evoke an answer by focusing the problem in ritual. Using their traditional symbolic system they represented the emperor to themselves in the familiar terms of divine power. The imperial cult, like the cults of the traditional gods, created a relationship of power between subject and ruler…The cult was a major part of the web of power that formed the fabric of society. (71)

Whatever the case, being worshiped in the various provinces gave Caesar the wonderful benefit of being able to maintain allegiance and order throughout his empire with little need to exert his military might. Messages and depictions of Caesar’s divine nature and ultimate authority permeated the empire, from the coins that changed hands day after day to public inscriptions or other forms of circulating literature. Virgil’s Aeneid, for one example, depicts Aeneas being shown the future destiny of the nation that would begin with him, including Julius Caesar and Augustus: “For there is Caesar, and all the line of Iulus, who are destined to reach the brilliant height of Heaven. And there in very truth is he whom you have often heard prophesied, Augustus Caesar, son of the Deified, and founder of golden centuries once more in Latium, in those same lands where once Saturn reigned.” (170). A similar depiction appears on the Priene calendar inscription, found on two stones at the city of Priene in western Asia Minor:

Since Providence, which has ordered all things and is deeply interested in our life, has set in most perfect order by giving us Augustus, whom she filled with virtue that he might benefit humankind, sending him as a savior, both for us and for our descendants, that he might end war and arrange all things, and since he, Caesar, by his appearance (excelled even our anticipations), surpassing all previous benefactors, and not even leaving to posterity and hope of surpassing what he has done, and since the birthday of the god Augustus was the beginning of good tidings for the world that came by reason of him. (Craig, 68)

The Greek word translated here as “good tidings” is εὐαγγέλιον (euangelion), which appears often in the New Testament as well, commonly translated as “gospel.” These are just some of the many ways that Caesar came to be described across the empire: lord, savior, a bringer of peace, one who cleanses sins, a son of god. These same distinguishing features are, of course, also applied to Jesus in the New Testament. This creates a potential image of conflict, with both figures claiming to embody essentially the same role. There are many passages in the New Testament in which scholars have suggested that implied connections to the imperial cult are present. It certainly seems likely that these are intentional on the part of the writers. The question remains, however, as to what the purpose is. Perhaps the intention is anti-imperialist political criticism against Roman domination, but the reality of the way in which Rome is depicted throughout the text seems to be far more subtle and complicated than that.

It is true that the early Christians were, at times, regarded with suspicion by their Roman neighbors, if not as an actual threat, at least as “religious fanatics, self-righteous outsiders, and arrogant innovators,” as Robert Wilken put it (63). Tacitus described Christianity as the “enemy of mankind.” In referring to this, Wilken also specified that Tacitus “did not simply mean he did not like Christians and found them a nuisance (though this was surely true), but that they were an affront to his social and religious world” (66). There is, perhaps, a distinction to be found here. While Christianity did present a social, religious, and cultural ideal that was quite different from the Roman ideal, did Christianity ever pose a political challenge as well?

It seems fair and rather obvious to state that the New Testament does not necessarily take a position of support regarding the rule of Caesar, but we do not necessarily find a clear attitude of hostility either. If anything, despite the Roman Empire serving as the backdrop for the entire New Testament narrative, Caesar is almost treated with a mild neglect in the text. The conflicts that Jesus encountered most often were from fellow Jews, such as the Pharisees. Likewise, the only accusations present in the New Testament regarding Jesus actively attempting to subvert Caesar’s authority also came from the Jewish religious leaders (Luke 23:2, John 19:12). However, even the Roman governor Pontius Pilate saw no validity to the claim that Jesus was a threat to Caesar (Luke 23:13-15). As Dean Pinter put it, “For Pilate the proclamation directed to Jesus is one of ‘King of the Jews’ and not ‘King of the Empire’ The title ‘King of the Jews’ may signal an upstart pretender to the local throne, but this is nothing like saying ‘here is another one claiming to be the emperor” (112). Similar accusations were also made against Paul and Silas in Thessalonica, but these accusations were also made by Jews rather than Romans (Acts 17:6-7), and Paul later claims that he has done nothing against the Jewish law or against Caesar (Acts 25:8).

There are numerous passages where Romans actually receive rather gracious depictions in the New Testament. Jesus praised the faith of the centurion in Matthew 8 and in Luke 7, and another centurion present at the crucifixion makes the claim, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39). This is a particularly striking claim to put in the mouth of a Roman centurion, considering the underlying contrast of Jesus and Caesar that is continually present. Passages such as these can certainly be complicated, because while they seem to grant respect to these Roman centurions, they also potentially seem to pit them against their own emperor in favor of Jesus.

However, there are also passages such as Romans 13, which have long sparked debate. “Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established” (Romans 13:1). An almost identical statement is made in 1 Peter as well: “Submit yourselves for the Lord’s sake to every authority instituted among men: whether to the king, as the supreme authority, or to governors, who are sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to commend those who do right” (1 Peter 2:13-14). I think the key to understanding the perspective presented in these passages lies in the fact that God is clearly presented as the ultimate authority, and therefore Caesar, as well as any other ruler, are to be seen by the readers of the New Testament as merely appointed subordinates. Similar claims are made regarding rulers in the Old Testament as well, such as Nebuchadnezzar and Cyrus (Jeremiah 27:6, Isaiah 45:1). In other words, political authority is ultimately derived from divine authority, and divine authority is the only one with which the New Testament chiefly concerns itself.

We see a prime example of this in the story of Jesus being questioned about paying taxes to Caesar. This story is present in all three of the Synoptic Gospels and is the only place in any of the gospels in which Jesus references Caesar directly. He calls attention to Caesar’s image on a coin and says, “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s” (Matthew 22:21, Mark 12:17, Luke 20:25). While Caesar’s image is on a small coin, God’s image is on each person (Genesis 1:26). Jesus highlights the higher reality which lay behind the comparatively insignificant political reality that was being addressed. In this call to give one’s life back to God as his image-bearer, Jesus emphasized that the way you live your life is of far greater importance than what ruler happens to be collecting taxes from you; because that ruler is simply another person who was created and appointed by God.

Therefore, the primary focus of the contrast between Jesus and Caesar presented in the New Testament is centered not on Caesar’s political rule, but on his supposed divine status. While the Biblical perspective is that the political is determined by the divine, the Roman perspective often appeared to be the opposite. Emperors who accomplished great things politically were the ones who would be deified by the Senate after they died, and not all emperors received this honor. Such a notion of the divine is drastically different than the Biblical perspective. However, in the Roman, polytheistic perspective the gods have many similar characteristics to humans, though they occupy a higher level. Paul Veyne stated that, “relations between men and deities resembled relations between ordinary men and such powerful brethren as kings or patrons” (210). The lines between the political and the divine in the Roman world were consistently blurred.

A clear distinction can be somewhat complicated to make; and S.R.F Price, for one, argues against the attempt to force a distinction between politics and religion, considering it to be a stumbling block to properly understanding the imperial cult, due to inserting Christian-based assumptions: “In modern times the preoccupation with this distinction is pervasive. Most scholars agree that the imperial cult was only superficially a religious phenomenon…The conventional formula is that the imperial cult was simply an expression of political loyalty” (51). This argument correctly recognizes that the Roman perspective did not see a significant distinction between politics and religion regarding the imperial cult, and it also recognizes that the Christian perspective did tend to make some level of distinction. However, what it fails to recognize is that the differing contrast between these two viewpoints is precisely the crux of the issue. Rather than one causing the other to be misunderstood, an understanding of both is necessary in order to grasp the fundamental dichotomy that lies between Christianity and the Roman world.

In a polytheistic world, adding a cult of emperor-worship amongst the large collection of other gods and goddesses is not a difficult concept to accept. But within a monotheistic framework such as Christianity, or Judaism before it, such idolatry presents a serious issue, and this is the issue that the New Testament addresses. Although the Roman world viewed the imperial cult in mostly political terms, the New Testament criticized it on religious grounds. If the goal of the New Testament writers had been to present a political, anti-imperialist message, with Jesus as a physical replacement for Caesar, they could have done so which much more clarity. Perhaps fear of reprisal kept them from being overt, forcing them to address the issue with more subtlety; or perhaps they had a different focus to their message, one that was more anti-idolatry than anti-imperialism. N.T. Wright argued that the New Testament writers were successful in using subtle, subversive language to undermine Caesar’s divinity without calling for civil disobedience. He stated that, “the subversive gospel is not designed to produce civil anarchy” (6).

Caesar is not the only “god” that is dealt with in the New Testament. In fact, the other gods of the Greek and Roman pantheon are addressed far more frequently. In the book of Acts Paul has numerous encounters with the worship of various gods. While he is in Athens, he is distressed at all the idols he sees (Acts 17:16), and in Ephesus a riot is started by craftsmen who made items for the cult of Artemis and were afraid of losing business due to Paul’s stance against idols: “This fellow Paul has convinced and led astray large numbers of people here in Ephesus and in practically the whole province of Asia. He says that man-made gods are no gods at all” (Acts 19:26). Even Paul himself, along with Barnabas, both attracted a crowd of people in Lystra who wanted to worship them as gods, identifying Barnabas as Zeus and Paul as Hermes. They, unlike Caesar, strictly refused this offer of deification: “Friends, why are you doing this? We too are only human, like you. We are bringing you good news, telling you to turn from these worthless things to the living God, who made the heavens and the earth and the sea and everything in them” (Acts 14:15).

It was the idolatrous habits of the Roman Empire which the early church fought against, rather than simply its politics. Although, again, from the Roman perspective, they may not have seen a significant difference. With politics and religion melded in the minds of the people, culture and society were melded with them as well. The early Christians may not have sought to subvert Rome in a political sense, but they were certainly divergent in a cultural sense. They did not fit into society in the same way. They did not participate in the cult sacrifices and the various celebrations of Caesar or the other local gods. They did not adhere to the typical rules of social status. Rich and poor, men and women, slave and free, they all gathered together to share their meals. E.A. Judge stated, “The followers of Jesus inherited from Judaism their sense of being a distinct community, a kind of nation of their own…Their aim was not to find their place in the world as it was. They brought with them ideas and practices which undercut the classical order” (155). Christianity stood out from the norms of society in a way that was not directly threatening, and yet still threatened to change everything. As Kavin Rowe succinctly put it, “New culture, yes—coup, no” (91).

Certainly, the New Testament claims that Jesus is Lord, and Caesar is not. But Caesar need not necessarily be overthrown because of this; he simply need not be worshiped. Nevertheless, there are certainly passages in the New Testament which assert that Rome is ultimately destined for destruction, particularly in the book of Revelation. Although symbolic language is used throughout the book, such as referring to “Babylon the Great,” most scholars accept that the original audience of the book would have naturally seen connections to their present realities in the Roman Empire lying within the symbolism. Many scholars also suggest that numerous references to Caesar are also present in the book, one prime example being the mark of the beast in Revelation 13. Some have pointed out that this refers most likely to Nero specifically, given that his name adds up in gematria to 666 (Wilson, 330).

However, while the Roman Empire mostly likely provides the background for the message of Revelation, the message itself goes beyond an attack on Rome or a prediction of its eventual demise. The greater point is that Rome is not significant; it is not divine, and neither is Caesar. Rome is merely an earthly kingdom with an earthly ruler, just as Babylon, or Persia, or Greece had been before it. They each have their unique features, some may be more or less successful and long-lasting than others, but in the end, they are all the same. They are all part of Nebuchadnezzar’s statue, and the whole thing is coming down (Daniel 2). From a biblical point of view all earthly kingdoms are, by definition, temporary and doomed one day to vanish; only the kingdom of God is eternal.

This is the reason why the New Testament does not need to depict Jesus or any of the early church leaders as presenting a threat to Caesar; because Caesar posed no true threat to them, other than the potential for the imperial cult—or some other form of idolatry—to lead people astray. At times these kingdoms may also have posed a physical threat, by conquering, subjugating, or persecuting the followers of God. The early Christians faced persecution at times from Rome, and the New Testaments repeatedly warns its audience that such persecution will surely come. However, the claim that is consistently present is that their victory will come in the end. The New Testament writers called their readers to endure those hardships by keeping that eternal perspective in mind, and that is the perspective with which Caesar and the Roman Empire are referenced throughout the text. The divine reality of God’s rule always supersedes the political reality of Caesar’s rule. Though both may exist simultaneously, only one will last. The temporary can never overcome the eternal.

Evans, Craig. “Mark’s Incipit and the Priene Calendar Inscription: From Jewish Gospel to Greco-Roman Gospel.” Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism, Vol. 1, 2000, 68-69.

Judge, E.A. Social Distinctives of the Christians in the First Century, edited by David M. Scholer, Hendrickson Publishers, 2008.

Pinter, Dean. “The Gospel of Luke and the Roman Empire.” Jesus is Lord, Caesar is Not, edited by Scot McKnight and Joseph B. Modica, InterVarsity Press, 2013, 101-115.

Price, S.R.F. “Rituals and Power.” Paul and Empire, edited by Richard A. Horsley, Trinity Press International, 1997, 47-71.

Rowe, Kavin. World Upside Down: Reading Acts in the Graeco-Roman Age. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by W.F. Jackson Knight, Penguin Books, 1958.

Wilken, Robert L. The Christians as the Romans Saw Them. Yale University Press, 1984.

Veyne, Paul. The Roman Empire. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 1987.

Wilson, Mark. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, vol. 4, edited by Clinton E. Arnold, Zondervan, 2002.

Wright, N.T. “Paul’s Gospel and Caesar’s Empire.” Paul and Politics: Ekklesia, Isarel, Imperium, Interpretation, edited by Richard Horsley, Trinity Press International, 2000.

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2006.