Gateways Into and Out of Benjamin and Jerusalem

by Devin M. Esch

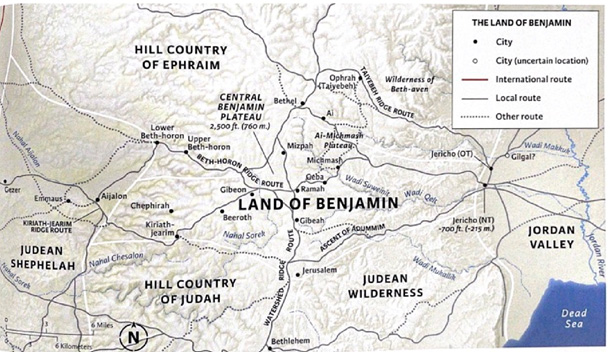

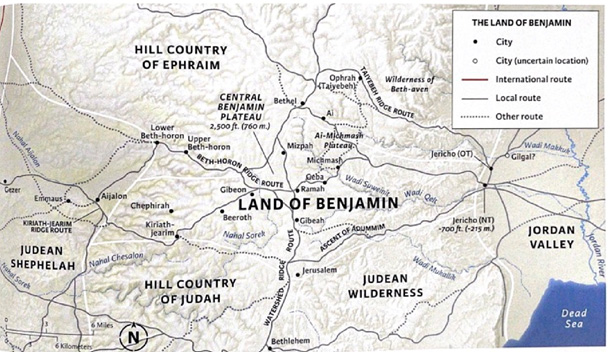

The Land Between has five major gateways that determine the flow of traders, people groups, and armies throughout the land. Examples of these gateways include the Phoenician and Carmel gateways, the Damascus, Bashan, and Hazor gateways, the Philistine and Negev gateways, the Arabian gateways. Perhaps none are as geographically and historically significant, however, as the gateways into and out of Benjamin and Jerusalem.

Overview of the Geography of Benjamin

The small land of Benjamin, belonging to the tribe of the youngest son of Rachel, acts as a horizontal wedge driven between the larger, more imposing tribes of Judah and Ephraim and Manasseh. Geographically, the tribal territory separates the southern hills from the central Hill Country. Benjamin’s tribal territory is approximately twenty-seven miles east-west and ten miles north-south at its greatest distances.

Overview of the Geography

Generally speaking, the land of Benjamin is enclosed by Kiriath-jearim on the west, Bethel on the north, Jericho and the Jordan River on the east, and Jerusalem on the south. The watershed ridge traverses the land like a spine, running north-south through the center of the territory and passing just west of Jerusalem. The hills of the land of Benjamin are pockmarked by three plateaus: the Bethel Plateau, the AiMichmash Plateau, and the Central Benjamin Plateau. All three of these names are modern in nature. The eastern side of Benjamin is Senonian chalk wilderness while the western side of the tribal allotment is uplifted Cenomanian-Turonian limestone. The annual rainfall totals vary greatly throughout the land of Benjamin — from an average of twenty-five inches of rain in the highest hills to only four inches of rain in Jericho. Thoroughly detailed border descriptions for the land of Benjamin are found in Joshua 15 and Joshua 18, evidence of the tribe’s unique geographical position within the larger Land Between. Even more detailed are the descriptions of the tribal territory in the areas surrounding Jerusalem.

The boundary then went up to Debir from the Valley of Achor and turned north to Gilgal, which faces the Pass of Adummim south of the gorge. It continued along to the waters of En Shemesh and came out at En Rogel. Then it ran up the Valley of Ben Hinnom along the southern slope of the Jebusite city (that is, Jerusalem). From there it climbed to the top of the hill west of the Hinnom Valley at the northern end of the Valley of Rephaim. From the hilltop the boundary headed toward the spring of the waters of Nephtoah…

By providing this detailed description of the borders, the biblical writer ensured that there would be no confusion regarding the tribal boundaries surrounding Jerusalem, a city with great significance to not only the tribe of Benjamin, but to the whole Land Between. Clearly Jerusalem was a city set apart from the others.

Before examining the geography of Jerusalem, it is important to understand the make-up of the broader lands in which this city is found. The Cenomanian-Turonian uplift found in the western half of Benjamin created hills and deep V-shaped valleys. This area is quite fertile due to the terra rosa soil that forms from the harder, bedded Cenomanian limestone. Most areas in western Benjamin receive more than enough rainfall — certainly over the twelve inches of rain required for farming — to allow for successful agriculture and crops. These rains primarily fall between October and March, providing the land with much needed relief from the intense summer heat. This combination of substantial rainfall with the terra rosa soil provides growing conditions that are ideal for olives, grapes, and almonds. Terraced farming is common in the hills of the western region of Benjamin due to the natural bedding of the Cenomanian Turonian limestone. These terraces were built for generational use, as each acre of terraced farm field took four to twelve years to build.

The Cenomanian-Turonian limestone holds water well, and rich springs and wells can be found scattered throughout the land of Benjamin. Dissolution cavities and other natural (and non-natural) rock cavities acted as cisterns to store the rainwater. All of these factors led to the emersion of numerous settlements throughout the hills, valleys, and plateaus of western Benjamin.

his western half of the land of Benjamin is drained toward the Mediterranean Sea by two major wadi systems: the Aijalon Wadi, which drains west, and the Sorek Wadi, which drains southwest. The Aijalon Wadi system is wider and less rugged than the Sorek Wadi system, although both systems are vitally important when it comes to draining and accessing the Central Benjamin Plateau. The watershed ridge separates the flow of water as it falls in the territory of Benjamin. All precipitation to the west of the ridge flows toward the Mediterranean Sea, while everything to the east flows toward the Jordan River and Dead Sea. The elevations of the hills in the area of Benjamin (2,600 feet) are lower than those hills north of Bethel and south of Jerusalem (3,000+ feet). This section of lower elevation creates a bit of a saddle in the watershed ridge adjacent to the Aijalon Valley, causing the land of Benjamin to act as a natural crossing point for those hoping to gain access to the opposite side of the watershed ridge.

Turning our attention to the eastern half of the tribal territory of Benjamin, it quickly becomes apparent that this half of the land is very different geographically. The Cenomanian-Turonian limestone uplift quickly transitions into Senonian chalk and Lisan marl, a thin and stony soil that is almost completely unproductive due to its high lime content. The Senonian limestone found on the “mountain slopes” between the hill country and the Jordan Valley is chalky, soft, and easily-eroded. This Senonian chalk erodes into deep canyons that make travel difficult, although chalk passes also can form that allow for easier passage. The soil is primarily used for herding animals since the lime-rich rendzina soil is too poor for most agriculture, unless mixed with the more fertile terra rosa soil in which case grains can be grown. Geographically, this region of Senonian chalk on the eastern side of the land of Benjamin slopes steeply downward from the heights of the hill country to the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea, the lowest place on earth, dropping 3,900 feet in elevation. The ground in this wilderness area is dry, barren, and harsh. Very little grows here, save for a few shrubby plants and some green grasses that break through the ground in the late winter and early spring after the rains, only to wither in the sweltering sun that quickly follows. This land receives less than twelve inches of rain per year, with much of the Senonian slopes receiving significantly less than that. The chalky ground is also poor at storing water, as the chalk simply erodes and collapses. All of these factors combine to cause very little permanent settlement in this area, with most of the residents being nomadic or seminomadic shepherds. While the land here is unforgiving, it was also of critical importance for the safety and prosperity of the tribal territory of Benjamin. A number of wadi systems traverse laterally through this land, draining the Bethel and Ai-Michmash Plateaus as well as the rest of the areas east of the watershed ridge. The Bethel Plateau in the north is drained eastward toward the Jordan River by the Wadi Makkuk, a rugged wadi system. The Ai-Michmash Plateau a bit south empties into the Zeboim Valley, a system that is much broader and gentler. The majority of the water from the eastern side of the watershed ridge, however, ends up flowing to the southeast and into the Wadi Suweinit, a tributary to the much larger Wadi Qelt.

Benjamin’s Three Plateaus

There are a number of very important cities and villages in the land of Benjamin, many of which are located on or around Benjamin’s three major plateaus. The Bethel Plateau is the northernmost plateau out of the three, a place where the watershed ridge flattens out a bit from its typically well-defined spine. Formerly called Luz, meaning “almond tree,” Bethel was an old Canaanite city-state whose new name meant “house of God.” The Bethel Plateau is small and relatively flat; it is also noticeably higher in elevation than the Central Benjamin Plateau to its south. Its soil is fertile and suitable for orchards, a fact that is perhaps reflected in the city’s original name. The plateau marks the northern border of the land of Benjamin, separating the rest of Benjamin from the land of Ephraim to the north.

Just southwest of the Bethel Plateau lies the Ai-Michmash Plateau. While plateau is named after its two major cities, Geba is also a significant site in the area. This plateau is less clearly defined geographically as the other two, yet the plateau still acts as a joining element for Ai, Michmash, and Geba. In the biblical texts, this easternmost area of permanent settlement was referred to as an emeq, meaning “broad valley.” Cenomanian-Turonian limestone and terra rosa soil make this plateau the last place for agriculture before the hills transition into the chalky Senonian wilderness to the east.

Moving west, the Central Benjamin Plateau dominates the heartland of the tribal allotment of Benjamin. It’s here that the watershed ridge widens into a flat, fertile plateau bordered by higher ridges to the east and south and deep canyons to the west.

The cities of Gibeah, Ramah, Mizpah, and Gibeon delineate the perimeter of the Central Benjamin Plateau. These cities are found on natural uplifts within or surrounding the plateau. Dr. Paul Wright illuminates this fact, pointing out that “each of these cities has a topographically appropriate name: Gibeon and Gibeah mean ‘low hill’; Ramah means ‘height’; and Mizpah means ‘lookout point.’” Establishing these cities on the gentle rises allowed the flatter areas of the Central Benjamin Plateau to be used for agriculture and farming. The Cenomanian-Turonian limestone that makes up the plateau produces fertile terra rosa soil. When this fertile soil is combined with the abundant rainfall that falls predictably on the plateau, some of the best agricultural land in the central hill country is produced. The Sorek and Aijalon wadi systems drain the Central Benjamin Plateau to the south and to the west, respectively.

Jerusalem’s Context within Benjamin

The tribal territory of Benjamin is undoubtedly an important area in the Land Between with a number of significant plateaus, wadis, and cities. No city within the borders of Benjamin — or within the entire land, for that matter — was as important as Jerusalem. There are countless events and stories, both biblical and extra-biblical, that happen in and around Jerusalem. To fully grasp the complexities of Jerusalem, the city’s geography and topography must first be understood. Jerusalem, by all topographical aspects, is a city that should not exist where it does. There are no natural features found in Jerusalem that typically define a major settlement location. Jerusalem is not located directly along a major route, has no river or harbor for trade, and has very little to offer in terms of product for export. In almost every aspect, Jerusalem should not be there.

Jerusalem is located in an area of Cenomanian-Turonian limestone, not too far away from where the land changes to Senonian chalk to the east. The topography of the land is hilly, with the deep valleys of the upper Kidron wadi system separating the rises. David established his city on the Southeastern hill, a sloping finger-like extension of the higher Eastern hill. Parallel to these two hills is the Kidron Valley, a valley that was much deeper in antiquity than it is in the present day. With the Kidron Valley lying at the bottom of its western slope, the Mount of Olives rises above the city to the east to a height of 2,661 feet, separating the hills of Jerusalem from the wilderness of Judah and Benjamin.

Jerusalem’s Western hill is noticeably higher and broader than the Eastern hill, topping out at 2,540 feet in elevation. These two hills are separated by the shallow Central Valley, called the Tyropoeon (“Cheesemakers”) Valley in the time of the New Testament. While Jerusalem started with David settling only on the Eastern hill, Jerusalem expanded as time went on to include both the Eastern hill and the Western hill. To the west of the Western hill, the Hinnom Valley (called Gehenna by Jesus) cuts through the landscape, it too an upper extension of the Kidron wadi system. These three valleys — Hinnom, Central, and Kidron — join together south of the city, draining Jerusalem in the direction of the Dead Sea. The watershed ridge lies just to the west of Jerusalem, deciding the final location of the twenty-four inches of rain that fall annually in this area.

The residents of Jerusalem used this rainfall to fill cisterns, making good use of the water-retaining qualities of the Cenomanian-Turonian limestone. The main natural source of water for the city of Jerusalem, however, was the Gihon Spring, which produces over 21 million cubic feet of water per year. A water system was dug in the days of Hezekiah in order to access the spring from within the city, evidence of Jerusalem’s reliance on this primary water source.

Jerusalem is surrounded by hills, its topography resembling a bowl or dish. This gives clarity to the Lord’s warning to the people of Jerusalem and Judah, saying, “I will wipe out Jerusalem as one wipes a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down.” These higher hills can provide its residents with a feeling of protection as well as a feeling of vulnerability, depending on who is controlling the lands surrounding the city. The steep valleys in Jerusalem help to provide some security, yet the city is not surrounded by valleys on all four sides. The northern approach is a gradual slope that leads directly down to the city from the watershed ridge about a half mile north. This topographical feature has been the reason that most of the attacks on Jerusalem have come from the north. It is also the reason that the northern approach to the city is the most heavily fortified.

Routes Through Benjamin

The land of Benjamin acted primarily as a buffer zone between larger powers to the north and the south as well as people groups from the east and west. Important highways and routes passed through this area, creating a unique situation for those residents who called this small tribal land their home. Due to the nature of Cenomanian-Turonian limestone, routes tended to stay along the tops of the ridges where possible, avoiding the deep V-shaped canyons. The major north-south route through Benjamin was the route which followed the watershed ridge, often referred to as the Patriarchal Highway. This road ran almost the entire length of the Land Between and was an important route throughout history. Jerusalem lies just to the east and beyond the upper reach of the rugged Sorek wadi system. This deep wadi caused traffic from the coast traveling in and out of Jerusalem to take a north-south route around the Sorek system rather than going directly east into Jerusalem. This northsouth route led into the Central Benjamin Plateau, heightening the importance of controlling this section of flattened terrain.

Benjamin had its easiest access to the coast via two main routes that followed the ridges between wadi systems: the Beth-horon Ridge Route and the Keriath-jearim Ridge Route. The Beth-horon Ridge Route was the much more important route of the two, acting as Jerusalem’s lifeline to the coast. This route skirted just north of the main branches of the Aijalon wadi system, the easiest wadi system to traverse between the Central Benjamin Plateau and the coast. This route connected Gibeon on the plateau to Aijalon at the base of the valley, passing by Upper and Lower Beth-horon. Further west, this route connected to the Joppa-Aphek-Gezer Triangle, which was “an international region… coveted by local powers in the hills, especially Jerusalem.” Anyone bringing an army or large group up from the coast into the hill country would find this route to be the most accommodating. The Keriath-jearim Ridge Route follows the ridge between the Aijalon and Sorek wadi systems, a much harsher terrain to traverse for armies interested in the Central Benjamin Plateau.

The plateau was guarded on the west by the city of Gibeon, a large site on a rise near the upper fingers of both the Sorek and the Aijalon wadi systems. Coming from the coastal plain up to the Central Benjamin Plateau, both the Beth-horon Ridge Route and the Keriath-Jearim Ridge Route converged near Gibeon. Naturally, this allowed Gibeon to act as the “front door” to Benjamin, and therefore Jerusalem. Practically all traffic traveling to and from the coast passes by this site. Whoever controlled the city of Gibeon controlled the Central Benjamin Plateau and therefore could regulate access to and from the coast and Jerusalem.

The eastern side of Benjamin, including the Bethel and the Ai-Michmash Plateaus, is accessed by three major routes that branch up through the wilderness and into the hill country. These east-west routes all originate in Jericho, causing the “world’s oldest city” to act as the “back door” to the land of Benjamin and Jerusalem. The northernmost of these routes is the Taiyebe Ridge Route, which follows the ridge separating the Auja and Makkuk wadi systems. This route passes by the biblical town of Ophrah (also called Ephraim) and ends at the Bethel Plateau. The central route that ascends into the hill country of Benjamin is the Zeboim Valley Route. This route follows the Zeboim Valley, a valley that is noticeably less rugged than the others. The route’s course traverses the Ai-Michmash Plateau and the cities of Michmash, Geba, and Ramah, ultimately intersecting with the Patriarchal Highway near the Central Benjamin Plateau. The southernmost route ascends along the top of the continuous ridge south of the Wadi Qelt and was called the Ascent of Adummim (“The Red Ascent” or Jerusalem’s “Jericho Road”). This steep and rugged Ascent led its travelers from Jericho to the Patriarchal Highway just north of the city of Jerusalem. This route used a small saddle in the Mount of Olives to make its final approach to the city. The convergence of these three routes at the oasis of Jericho made the city invaluable to the safety and security of the land of Benjamin. Anyone who wanted to access the Transjordan from the central hill country of the Land Between would have had to pass by Jericho. The reverse is also true, as armies hoping to capture the land of Benjamin would have to first take Jericho in order to access the routes. Jericho is the undoubtedly the best and most strategic entry point from the east into the hill country. Going further, it is also the best way for an army to take the entire Land Between.

Judges 3:12-30: The Contexts of the War of Ehud within Benjamin

An understanding of the topography of the land of Benjamin provides a basis for deeper realizations into the movements of people and motivating factors behind many familiar biblical events. The war of Ehud in Judges 3:12-30 is one of these events that gains richness when the geography is understood. According to the biblical text, “the Israelites did evil in the eyes of the Lord, and because they did this evil the Lord gave Eglon king of Moab power over Israel.” Moab was located across the Rift Valley in Transjordan, occupying the land directly east of the Dead Sea. Eglon summoned the help of the Ammonites and the Amalekites, tribes located north of Moab and south of the biblical Negeb, respectively, and they attacked the land of Israel and captured the City of Palms, known today to be Jericho. Eglon knew the geographical importance of Jericho, and in order to attack the land of Israel, he knew his first stop would need to be Jericho.

The text mentions “the Israelites were subject to Eglon king of Moab for eighteen years.” Interestingly, the Bible never mentions Eglon pushing any further into the land of Israel, and yet the Israelites were subject to him. Now perhaps this mention of “Israelites” refers only to those living in Jericho at the time, but a broader use of the term is much more likely, referring to all the Israelites living in the hill country of Benjamin. Controlling Jericho meant Moab had control of all travel to and from the land of Benjamin and beyond. This includes all trade as well. Without access to trade routes in the Transjordan, the Israelites living in the hill country would have been economically hampered, certainly a reason to cry out to the Lord as they did in Judges 3:15. The Lord gave the people a deliverer in Ehud, described as “a left-handed man, the son of Gera the Benjamite” (an ironic trait due to the fact that Benjamin means “son of the right hand” in Hebrew). He was sent by the Israelites with tribute to Eglon, who was likely in Jericho at the time. If we assume Ehud was living in the hills of Benjamin, he likely took the Zeboim Valley Route downwards to Jericho.

Ehud presented the tribute to Eglon king of Moab and he and his men went on their way. It’s interesting to note that the men and Ehud travelled north to Gilgal, a town slightly northeast of Jericho. We would have expected them to return to the hill country of Benjamin by one of the three routes to the west, so their movements towards Gilgal are a bit odd. Regardless, Ehud left his men and returned to Jericho, informing Eglon that he had a secret message for him. Ehud proceeded to stab the overweight king Eglon with a double-edged sword, leaving him to die in the locked upper room of the palace.

Ehud fled to Seirah, which is likely a forest in the hill country of Ephraim, just north of the tribe of Benjamin and perhaps in the vicinity of Bethel. Ehud’s escape route up into the hill country was probably the Taiyebe Ridge Route, leading him to the safety and familiarity of the hills and his own people. He could have stayed there and ended his mission, having successfully killed the king of Moab. However, Ehud knew that the job was not finished and the land would not be secure unless they completely recaptured Jericho. He summoned the Israelites and led them down one of the routes (perhaps the Zeboim Valley Route again; the text is unclear) toward the city of Jericho.

The biblical text says they “took possession of the fords of the Jordan that led to Moab; they allowed no one to cross over. At that time they struck down about ten thousand Moabites… not one escaped. That day Moab was made subject to Israel, and the land had peace for eighty years.” While the text does not explicitly state that the Israelites captured Jericho, it seems likely that they did. Ehud knew the significance of the city for the land of Benjamin, so it would have been a high priority for recapture. The text does state that the Israelites took control of the fords of the Jordan that led to Moab. Possessing this Jordan River crossing would have given the Israelites complete control over everyone coming and going through this region. The text seems to indicate that the Israelites took control of the ford before killing the Moabites. This would mean they probably skirted around Jericho — perhaps splitting and taking a group to the north of the city near Gilgal, a place Ehud and his men would have been familiar with — and captured the ford, cutting off Moabites from any route of escape across the Jordan. They could then descend on the city of Jericho and drive the Moabites out; they would have nowhere to flee. The Israelites now controlled their all-important “back door” again, and there was peace and security because of it.

Joshua 9:1-10:15: The Contexts of the Gibeonite Deception within Benjamin

Turning to Benjamin’s “front door,” the story of the Gibeonite deception and the sun standing still in Joshua 9:1-10:15 becomes more clear when we place the events on a map. The narrative in Joshua 9 begins with the kings of the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites coming together to form a coalition to attack Joshua and Israel. The cities of these people groups are located primarily in the hill country, western Shephelah, and along the coast. The Gibeonites living in the Central Benjamin Plateau realized that they were up against Joshua and the God of the Israelites, and they remembered the promise God made to Moses, saying all the inhabitants of the land would be wiped out. Through trickery, they made an alliance with Joshua and the Israelites in Gilgal, just northeast of Jericho. They likely took the Zeboim Valley Route, past Ramah, Geba, and Michmash. The Israelites were furious when they found out about the ruse and they tried to attack the Gibeonites. Joshua kept the covenant that was made before God, however, and saved the Gibeonites from the Israelites. They didn’t get off totally free though, as Joshua made the Gibeonites woodcutters and water carriers for the assembly as punishment.

Adoni-Zedek king of Jerusalem, in Joshua 10, became alarmed that the people of Gibeon had made a treaty with Joshua and the Israelites. He was concerned because “Gibeon was an important city, like one of the royal cities.” Adoni-Zedek knew that Gibeon’s alliance with Israel could mean a loss of control of the Central Benjamin Plateau and the routes leading to the coast. Losing Gibeon due to a treaty with the Israelites meant the king of Jerusalem no longer controlled the main approach to the hill country from the coastal plain via the Beth-horon Ridge Route. In an attempt to prevent this from happening, Adoni-Zedek appealed to his fellow Amorite kings in Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon, who joined forces to march against Gibeon and attacked the city.

The Gibeonites sent a cry for help to Joshua and his army in Gilgal, pleading for them to not forget their treaty. Joshua took all of his men and marched throughout the night up the Zeboim Valley Route from Gilgal to Gibeon, a total distance of approximately eighteen miles. The normal journey took two to three days, as seen in Joshua 9:17, so the urgency that the Israelite army had is apparent. The Amorite army attacking Gibeon would not have expected the Israelite army to arrive so quickly, and they were surprised on their eastern side. Now they had the men of Gibeon guarding the western edge of the Central Benjamin Plateau and the Israelite army approaching from the eastern side of the plateau, removing any hope for a successful siege and escape. The Israelites defeated the Amorites at Gibeon and pursued them down the Beth-horon Ridge Route. They could not have fled down the Keriath-jearim Ridge Route because the cities along this route were controlled by the Gibeonites; the Beth-horon Ridge Route was their only hope for escape. The text says they were cut down all the way to Azekah and Makkedah, sites in the Shephelah to the south. The Lord sent large hailstones that killed many of the fleeing Amorites as they tried to escape down the road from Beth-horon to Azekah. The Lord was clearly fighting for Israel as He made the sun stand still over Gibeon and the moon over the Valley of Aijalon at the request of Joshua. Joshua and his men then returned to Gilgal, perhaps by way of the Patriarchal Highway. The Israelites now had control over the Central Benjamin Plateau and its access to the coastal plain, as well as the routes leading past Jericho to the Transjordan. This created an area of Israelite control through the middle of the land of Benjamin that afforded them access to all regions of the land.

Amos 5:4-6: Benjamin in Prophecy

The prophet Amos — who interestingly never considered himself a prophet but rather a shepherd and a grower of sycamore-fig trees — used the land of Benjamin to enrich his lament and call to repentance toward the Israelites.

This is what the Lord says to Israel: ‘Seek me and live; do not seek Bethel, do not go to Gilgal, do not journey to Beersheba. For Gilgal will surely go into exile, and Bethel will be reduced to nothing.’ Seek the Lord and live, or he will sweep through the tribes of Joseph like a fire; it will devour them, and Bethel will have no one to quench it.

This passage is a call to repentance, and Amos brings in familiar imagery and sites in order to make his point. The Israelites were scored by Amos for their apostasy at Bethel. Bethel, meaning “House of God,” was a major sanctuary site for the northern kingdom of Israel. It sat on the border between the tribes of Benjamin and Ephraim and was one of the higher ridges in the area. Jacob consecrated the location as a place to worship God and built an altar to God there many years later. The ark of the covenant was kept there for a time and the city remained as an important worship center in Israel. The Israelites began straying from their worship of God, however, and golden calves were set up at Bethel and Dan. Amos condemned Bethel as a place of idolatry, encouraging the Israelites to repent and seek God rather than seeking Bethel and its pagan idols. The Israelites likely would have been familiar with the journey to Bethel in the hill country, making the ascent to worship God or gods, depending on their hearts. Amos suggests that these cities are temporary; they will be reduced to nothing and will be sent into exile. However, the Lord is kind and will be faithful to them. He warns that if they turn from God and do not seek him, he will sweep through the tribes like a fire, “and Bethel will have no one to quench it.” Bethel was not an overly lush area, but being in the hill country, it certainly had vegetation and crops that would be burned up in a fire. There are several natural springs in the area of Bethel due to its location in the Cenomanian-Turonian hills, so typically there would be an abundance of water with which one could extinguish a fire. Amos specifically warns the Israelites that despite their abundant water, there would be no one to quench the fire. God is the only one who is forever and who can provide life to the straying Israelites should they seek Him.

Psalm 125:2: Benjamin in the Psalms

The writer of the psalms was clearly familiar with the topography and geography of the Land Between, specifically that of Jerusalem. “As the mountains surround Jerusalem, so the Lord surrounds his people both now and forevermore.” As previously mentioned, Jerusalem is surrounded by hills that are higher than the city itself. This gives the impression of a bowl, with Jerusalem on a small rise in the middle. The people living in Jerusalem certainly would have felt the protection that the hills afforded. At times, however, the hills could make Jerusalem feel vulnerable, giving the enemies the high ground all around the city. It is important to note that the psalmist does not make a distinction here; they simply relate the hills surrounding Jerusalem to the way the Lord surrounds his people. That being said, it is fair to assume that this comparison was meant in a positive, comforting light.

The land of Benjamin was a vitally important gateway throughout the history of the Land Between. Benjamin’s three plateaus, diverse topography, and connecting routes make this small tribal territory valuable and desirable. The prophets and psalmists used its land and routes to enhance their messages. Jerusalem acts as the magnetic center of Benjamin, eventually becoming David’s chosen capital city. Perhaps none of the gateways in the entire Land Between are as significant as the gateways into and out of the land of Benjamin and Jerusalem.

Bibliography

Aharoni, Yohanan. Carta Bible Atlas. 5th ed. Jerusalem: Carta, The Israel Map & Publishing Co, 2011.

Historical Geography Fieldbook. 3rd ed. Jerusalem: Jerusalem University College, 2020.

Monson, James M. Geobasics in the Land of the Bible: Maps for Marking. Rockford, IL: Biblical Backgrounds, Inc., 2008.

Monson, James M. Regions on the Run: Introductory Map Studies in the Land of the Bible. Rockford, IL: Biblical Backgrounds, 2019.

Van Pelt, Miles V, and Gary D Pratico. The Vocabulary Guide to Biblical Hebrew. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003.

Wright, Paul H. Holman Illustrated Guide to Biblical Geography: Reading the Land.

Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group, 2020.